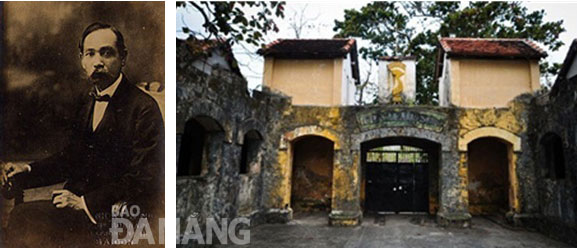

In 1908, following the Central Vietnam Uprising, patriot Phan Chau Trinh was arrested by the French colonial authorities in Hanoi and brought back to Hue for trial. Both the French Resident-Superior and the Nguyen court sought the death penalty.

Thanks to the intervention of progressive French officials and members of the Human Rights Association in Hanoi, the sentence was reduced to: “Death penalty, exiled to Poulo Condor; not eligible for pardon.”

This marked the beginning of his three-year exile on Con Lon (Con Dao), where he left a profound legacy of courage, dignity, and compassion.

Unyielding Spirit in Exile

Phan Chau Trinh was the first political prisoner ever exiled to Con Dao — a place previously reserved only for common criminals. His manner, speech, and bearing immediately distinguished him from other inmates. Guards and prisoners alike referred to him as “the high-ranking official.”

The French attempted to “soften” him with special treatment: no prison uniform, no forced labor, daily walks outside the cell, and later permission to live in An Hai village. Yet none of this altered his steadfast patriotism.

During this time, he composed the renowned poem “Breaking Rocks in Con Dao”, a declaration of resilience for generations of political prisoners:

To be a man amid Con Lon’s mountains and seas,

Let the world shake with every strike of the hammer…

His refusal to bow was evident in every situation. When a guard accused him of insulting soldiers, the chief warden attempted to beat him. Phan Chau Trinh seized the rattan cane and snapped it in half — an act that led to seven days in shackles, but never broke his spirit.

Even when living outside the prison, he continued to defy coercion. Local officials disliked him for refusing to submit to arbitrary rules. When they reported him, he declared boldly:

“The demon of tyranny fears the god of freedom within me.”

He voluntarily returned to the prison barracks during a deadly epidemic — completely unfazed.

Loyalty and Brotherhood

Upon hearing that Huynh Thuc Khang and other patriots had been exiled to the island, Phan Chau Trinh immediately sent secret messages of solidarity. In a note smuggled through a prison window, he wrote:

“Hearing you have arrived, I stamped my foot to the heavens!

For the sake of our nation, this is a place to endure with pride, not sorrow.”

When guards confiscated Huynh Thuc Khang’s books, Phan Chau Trinh secretly bought them back and had them smuggled into the cell — giving the new political prisoners precious materials for learning French.

Years of hardship strengthened their camaraderie. Huynh Thuc Khang recalled the first time they met in person after months of imprisonment: both gaunt, grey, and exhausted. They simply looked at each other and laughed — a moment of shared resilience in the face of suffering.

Phan Chau Trinh also honored fellow prisoners who died on the island. When scholar Duong Truong Dinh passed away from illness, he visited the grave and wrote a moving elegy dedicated to his comrade.

A Legacy of Courage

Phan Chau Trinh’s years on Con Dao revealed a man of extraordinary moral strength — one who upheld freedom, justice, and integrity even in chains. His presence inspired political prisoners for decades, shaping the early legacy of resistance on Con Dao.

He is remembered today not only as a patriot and reformer, but also as the first political exile on Con Dao, whose courage helped ignite the spirit of struggle on the nation’s most infamous prison island.