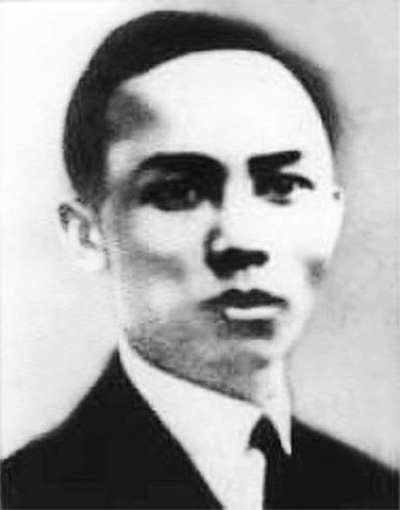

For generations of Vietnamese people, Côn Đảo is a place of legend—at once a symbol of colonial brutality and a sacred reminder of the unyielding will of countless revolutionaries. Among the most remarkable figures imprisoned here was Lê Hồng Phong, a distinguished leader of the Vietnamese Communist movement and a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International.

Born in 1902 in Hưng Thông commune, Hưng Nguyên district, Nghệ An province, Lê Hồng Phong grew up in a poor peasant family in a region long known for its revolutionary spirit—from the Cần Vương movement to the campaigns led by Phan Bội Châu. After completing elementary studies, he left his village to work in Vinh and Bến Thủy. In 1924, he and several compatriots traveled to Guangzhou, China, where the “Tâm Tâm Society”—including Phạm Hồng Thái, Hồ Tùng Mậu, Lê Hồng Sơn and others—sought to revive the weakening patriotic movement. When Nguyễn Ái Quốc arrived in Guangzhou later that year, he established the Vietnam Revolutionary Youth League and opened political training courses. Lê Hồng Phong was one of the first students, embracing Marxism–Leninism and the cause of proletarian revolution.

From 1924 to 1931, he studied at the Whampoa Military Academy, joined the Communist Party of China, and was later sent by Nguyễn Ái Quốc to the Soviet Union. There he studied military aviation theory in Leningrad and underwent pilot training at Borisoglebsk before entering the Communist University of the Toilers of the East. He became a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and participated in organizing the Indochinese communist nucleus. After three years, he returned to Asia and, in 1931, was assigned to support the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Indochina.

In 1935, he attended the Seventh Congress of the Communist International, delivering a detailed report on Indochina’s revolutionary situation, exposing French colonial repression, and evaluating the Party’s leadership. With his clear strategic vision and principled self-criticism, he convinced the Comintern of the movement’s potential. The Congress elected him as a full member of its Executive Committee and recognized the Communist Party of Indochina as an official section of the Comintern. The same year, he chaired the First Congress of the Party in Macau.

In June 1939, French agents arrested him in Saigon. After his prison term expired, he was exiled under surveillance to his hometown. Despite harsh repression, he continued to write and contribute to the theoretical struggle. In early 1940, the French arrested him again and imprisoned him at Khám Lớn Sài Gòn. On August 27, 1940, a colonial court sentenced him to five years of imprisonment and ten years of house arrest, accusing him of being the ideological leader of the Southern Uprising.

At the end of 1940, he was deported to Côn Đảo and registered under prisoner number 9983. There he endured relentless forced labor, solitary confinement, and brutal torture in Banh 2—sometimes in Cell 19, sometimes in the infamous solitary Cell 5. Despite extreme hunger, illness, and the enemy’s cruel attempts to silence him, he remained steadfast. Guards beat him at any moment—during work assignments, bathing, roll call, even during meals. Yet stories of his courage spread throughout the prison; one episode in which he calmly continued eating while blood from fresh wounds mixed with his rice later became a powerful symbol in literature and art.

Inside this “hell on earth,” communist prisoners turned Côn Đảo into a school of revolutionary theory. Lê Hồng Phong organized clandestine political study sessions and inspired comrades with unwavering belief in the Revolution’s eventual victory. In these conditions—without paper or ink—he composed the celebrated “Red Nghệ An Rhapsody,” dictating each line to prisoner Nguyễn Tấn Miêng, who memorized it for more than 40 years before it was transcribed and published in 1985.

As his health deteriorated from dysentery caused by starvation rations and deliberate medical neglect, colonial authorities intensified efforts to isolate and eliminate him. He was locked alone in a pitch-dark cell barely two meters long, chained day and night. Fellow prisoners attempted to smuggle medicine to him but the guards confiscated everything.

After days of agony, at noon on September 6, 1942—his 40th birthday—Lê Hồng Phong died in solitary confinement, remaining defiant to his last breath. Before passing, he left a final message:

“Please send my greetings to all comrades. Tell the Party that until the final moment, Lê Hồng Phong kept absolute faith in the glorious victory of the Revolution.”

In just 40 years of life and 20 years of continuous revolutionary activity, Lê Hồng Phong devoted everything to the cause of national liberation. His life embodies moral integrity, loyalty to the Party, love for the people, and steadfast commitment to independence and freedom. Today, his name is forever etched into the collective memory of the nation—a shining example of courage, virtue, and revolutionary conviction.